Lennox Head News

ANOTHER DEAD WHALE FOUND ON SEVEN MILE BEACH IN LENNOX HEAD

Published

7 months agoon

By

Liam

ANOTHER DEAD WHALE FOUND ON SEVEN MILE BEACH IN LENNOX HEAD

By Sarah Waters

Whale deaths in the Northern Rivers region have become an unusually common occurrence in the past few months with another dead baby whale found at Seven Mile Beach in Lennox Head last Sunday.

The baby humpback had been attacked by sharks and was removed by Ballina Shire Council with the help of Jali Local Aboriginal Land Council.

There has been a spate of whales washed up on Northern NSW beaches since July.

On July 1, a six-metre, 30-tonne adult humpback whale died on Seven Mile Beach before the tide could take it back out to sea, despite a large-scale rescue operation.

In the same month, a humpback whale calf, believed to be just a few days old with its umbilical cord still attached, washed up alive on the same beach.

It was euthanised after marine vets determined it was too young to survive without its mother, even if it could be refloated back into the ocean.

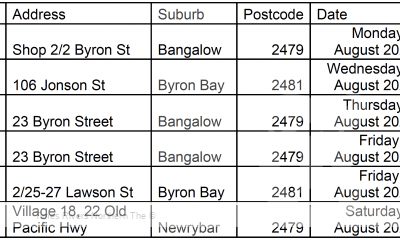

Last Wednesday, October 4, a juvenile humpback was found dead at Tallow Beach, in Byron Bay, at about 7am.

The popular surfing beach was closed by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) while the whale was removed and taken away to be buried.

Founder and chief executive of Byron Bay Wildlife Hospital Dr Stephen Van Mil has worked in the region for the past 10 years and said up until this year, he had never seen a dead or stranded whale on the NSW far north coast before.

He believed there were a number of factors which could cause the whales to beach in the region.

“Whale numbers generally are high, which is great news, but we’re certainly seeing a lot more migration traffic,” Dr Van Mil said.

“Of more concern is rising ocean temperatures.

“Normally, whales migrate north during our winter to find warm waters to calve – those warm waters are here, and calving’s have been observed around Port Macquarie, Coffs Harbour and Byron Bay.

“We believe that with bigger numbers and calving’s occurring in unusual locations, the whales are literally landing in trouble – nets, predatory sharks, boats, tides and currents add to the issues,” he said.

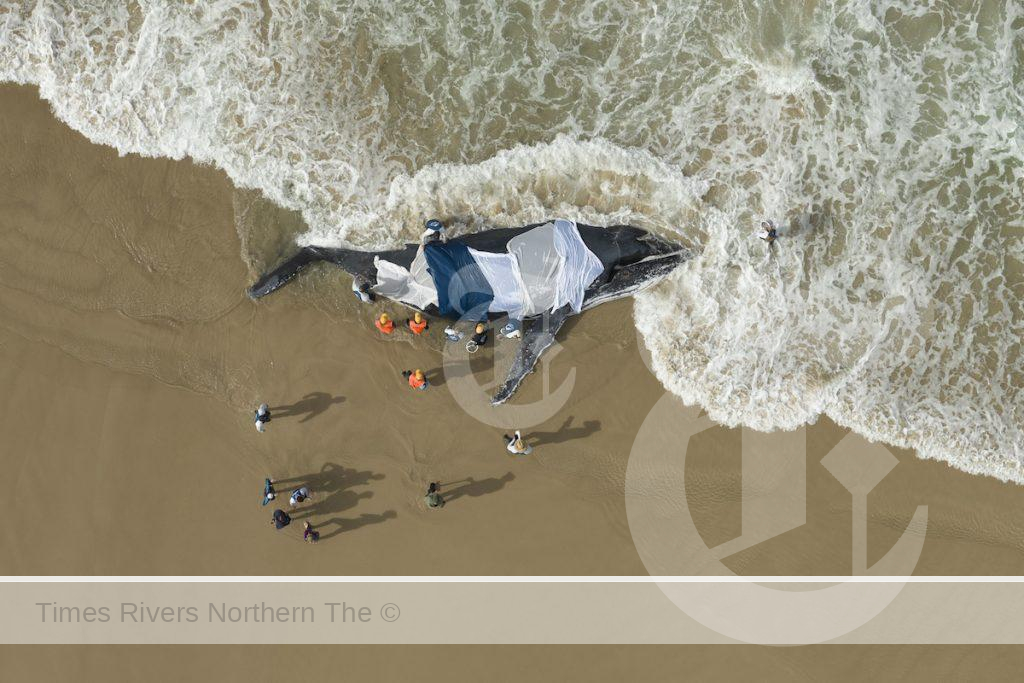

The beached Whale on Seven Mile Beach, Lennox Head.

Dr Van Mil attended the stranding of the 30-tonne adult humpback whale that died on Seven Mile Beach on July 1.

He and his team from Byron Bay Wildlife Hospital worked with volunteer group ORRCA (Organisation for the Rescue and Research of Cetaceans in Australia) and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service to take the whale’s bloods every hour, keep it hydrated and sedated.

It was hoped the whale could be refloated back into the open ocean once the tide came in, but unfortunately the whale died an hour before high tide.

Dr Van Mil said the humpbacks were coming close to the shore and sometimes when they’re chasing food, they can go over a sandbar and can’t get back to the open ocean.

In other instances, if they’re unwell, they can become weak and disoriented and get pushed in through tidal movements.

“For an individual animal it is a case-by-case basis – did it get injured, was it a calf that got separated from its mother by predating animals – all those things come into play,” he said.

“But they’re not supposed to be birthing in the waters that they are.

“There’s no argument that the ocean temperatures are rising.

“Those temperatures are telling their metabolic clocks that it is time to calve and they’re calving in the wrong locations.

“Recently on the Gold Coast a whale calf got caught up in netting and the mother was hanging around, she was distressed because the baby was caught up and couldn’t move with her.

“This is what happens when we’re changing the face of our natural environment and there’s consequences.

“When you’re trying to explain these recent strandings, the rise in the ocean temperature is probably the biggest contributing factor.”

A record number of humpback whales have been sighted migrating up the NSW coast this year.

Current estimates for the humpback population migrating up the east coast have been anywhere from 30,000 – 50,000 whales.

Humpback whales pass Australia’s east coast during their annual migration from Antarctica to the Great Barrier Reef.

After a summer of feeding on krill in Antarctic waters, the whales migrate north to their subtropical breeding grounds off the Queensland coast.

Humpbacks can be seen heading north between May and July and from September to November, on their way back to the Antarctic.

Humpback whales travel up to 10,000km during the migration.

Groups of young males typically lead the migration while pregnant cows and cow-calf pairs are at the rear.

For more local Lennox Head news, click here.

You may like

-

The Northern Rivers Times Newspaper Edition 199

-

Anzac Day Services Northern Rivers – Comprehensive Guide for the Region

-

Jewellery Design Centre Launches “Tell Our Stories” to Celebrate Lismore’s History

-

Lifeline Opens Northern Rivers Warehouse and Shop in Goonellabah

-

Green thumbs take note!

-

Most recent fish kill points to an unhealthy river

Alstonville News

Anzac Day Services Northern Rivers – Comprehensive Guide for the Region

Published

2 weeks agoon

24 April 2024By

Liam

Anzac Day Services Northern Rivers – Comprehensive Guide for the Region

This Thursday April 25, 2024, communities across our region will come together to commemorate Anzac Day with various services and marches. Here’s what’s planned for each area:

Richmond Valley

Casino:

- Dawn Service: Assemble at 5:15 AM on Canterbury Street at the Casino RSM Club. The march to the Mafeking Lamp starts at 5:30 AM.

- Mid-morning Service: Gather at 10:00 AM in Graham Place for a 10:15 AM march to Casino RSM Club.

- Evening Retreat: A brief service at 4:55 PM at the Mafeking Lamp.

Coraki:

- Assemble at 10:00 AM at the Coraki Hotel for a 10:30 AM march to the cenotaph in Riverside Park.

Broadwater:

- Community Dawn Service at 5:30 AM at Broadwater Community Hall, followed by a community breakfast.

Evans Head:

- Dawn Service: Gather at 5:20 AM on Woodburn Street near the bus stop, marching to Memorial Park for a 5:30 AM service. Breakfast at the RSL Club Evans afterward.

- Day Service: Assemble at 10:00 AM on Park Street, marching at 10:30 AM to Club Evans in McDonald Place.

- Additional Services: A bus departs the RSL at 8:00 AM for services at the memorial aerodrome and war cemetery, with a special flyover by the Amberley Air Force.

Rappville:

- Dawn Service at 5:30 AM at the Anzac Memorial on Nandabah Street.

- Day Service: Gather at the Rappville Post Office at 10:30 AM for an 11:00 AM service at the same memorial.

Woodburn:

- Assemble at 9:45 AM at the old Woodburn Post Office, marching at 10:00 AM to the memorial in Riverside Park for a service.

Kyogle LGA

Kyogle:

- Dawn service at 5:30 AM at the cenotaph.

- Assemble at 9:15 AM for a 9:30 AM march through the town center, concluding with a 10:00 AM service at the cenotaph.

Woodenbong:

- Dawn service at 5:15 AM at the Woodenbong water tower, followed by a Gunfire Breakfast.

- Gather for a 10:40 AM march to the Woodenbong Public Hall for an 11:00 AM Anzac Memorial Service. The day concludes with a wreath-laying at 11:45 AM and a Diggers Luncheon at 12:30 PM at the RSL Hall.

Bonalbo:

- Dawn service at 5:30 AM at Patrick McNamee Anzac Memorial Park, followed by a Gunfire Breakfast at the Bonalbo Bowling and Recreation Club.

- An 11:00 AM service at the Bonalbo Community Hall.

Old Bonalbo:

- A 9:30 AM service at Old Bonalbo Soldiers’ Memorial Hall.

Tabulam:

- Gather at 10:30 AM on Clarence Street for a march to the Light Horse Memorial, where a service and wreath laying will take place at 11:00 AM, followed by refreshments at noon at the Tabulam Hotel.

Mallanganee:

- A service and wreath-laying ceremony at 11:00 AM at Memorial Park.

LISMORE

Returned and Services League of Australia – City of Lismore sub-Branch ANZAC Day Committee wishes to invite the community to Lismore’s ANZAC Day March and Services, commemorating the fallen from Gallipoli and all other subsequent wars and deployments in which Australian Defence personnel have been involved.

At 5am the traditional Dawn Service will be held at the Lismore Cenotaph, following the March from the “Old Post Office Corner” on the corner of Magellan and Molesworth Streets.

The main March will commence at 9am and will depart Browns Creek Carpark, proceeding along Molesworth Street to the Lismore Memorial Baths. Followed by the ANZAC Day commemorative service at the Lismore Cenotaph.

The Lismore City Bowling Club will host a breakfast for veterans, families and community members.

Clarence Vally

Below is information that has been provided to Council by RSL Sub-branches across the Clarence Valley. If you are wishing to lay wreaths, please contact the sub-branch organiser for your area.

RAMORNIE (Sunday, 21 April)

- 10:45am – Ramornie Cenotaph

Contact: Barry Whalley – 0428 432 014

GRAFTON (ANZAC DAY Thursday, 25 April)

- 5:50am – Muster at Memorial Park

- 6:00am – Dawn Service at Memorial Park

- 6:30am – Gunfire breakfast at GDSC – $10pp (donated to charity)

- 9:30am – March from Market Square

- 10:00am – Commemoration Service at the Cenotaph, Memorial Park

Contact: Denis Benfield – 0412 410 474

SOUTH GRAFTON (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 4:50am – March from New School of Arts

- 5:00am – Dawn Service at the Cenotaph, Lane Boulevard

- 7:00am – Gunfire breakfast at South Grafton Ex-Servicemen’s Club

- 10:50am – March from New School of Arts

- 11:00am – Commemoration Service at the Cenotaph, Lane Boulevard

- Contact: Barry Whalley – 0428 432 014

ULMARRA (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 10:40AM – Muster for march at Ulmarra Cenotaph

- 11:00am – Commemoration Service at Memorial Park

- Contact: Robert McFarlane – 0407 415 923

CHATSWORTH ISLAND (ANZAC Day, Thursday 25 April)

- 5:15am – Dawn service at the Cenotaph

Followed by a sausage sizzle

Contact: John Goodwin – 0419 282 555

COPMANHURST (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 10:45am – Commemoration Service at Copmanhurst Memorial Cenotaph

Contact: Denis Benfield – 0412 410 474

GLENREAGH (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 5:30am – Dawn Service at the Glenreagh School of Arts

- Followed by a cooked breakfast in the hall (donation)

Contact: Noel Backman – 0434 197 994

HARWOOD (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 5:15am – Muster at Harwood Hall

- 5:30am – Dawn Service at Harwood Cenotaph in River Street

- Followed by Gunfire breakfast in the Harwood Hall (donation)

Contact: Helen Briscoe – 0431 677 110

Barry Smith – 0427 469 495

ILUKA (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 5:30am – Commemoration service

BBQ provided after service – outside hall (donation) - 10:30am – March from Iluka Public School

- 10:45am – Commemoration Service and wreath laying

Followed by free morning tea - Contact: Phil Bradmore – 0448 465 269

LAWRENCE (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 5:45am – Muster at Lawrence Hall for march to Memorial Park

- 6:00am – Dawn Service at Memorial Park

- 9:45am – Muster at Lawrence Hall for march to memorial park

- 10:00am – Commemoration Service at Memorial Park

- Contact: Bryan Whalan – 0417 232 809

LOWER SOUTHGATE (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 3:00pm – Commemoration Service at Lower Southgate War Memorial, Doust Park

Contact: Pauline Glasser – 0419 986 554

MACLEAN (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 5:30am – Dawn Service at Cenotaph

- 10:40am – March from Esplanade

- 11:00am – Commemoration Service at Cenotaph

Followed by lunch at Maclean Bowling Club (members only) - Contact: Trevor Plymin – 0415 400 658

TULLYMORGAN (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 5:15am – Muster for march at Tullymorgan School

- 5:20am – Dawn Service at the Tullymorgan School

Followed by gunfire breakfast (gold coin donation) - Contact: Sue Searles – 0408 408 749

WOOLI (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 5:30am – Dawn Service at the Cenotaph

- 6:00am – Breakfast for those attending the Dawn Service at Wooli Bowling & Recreation Club (gold coin donation)

- 10:45 am – Assemble at Wooli Bowling & Recreation Club for march

- 11:00am – Commemoration Service at the Cenotaph

Lunch for ex-service personnel and partners at the Wooli Bowling & Recreation Club - Contact: Brian Frederiksen – 0421 077 718

YAMBA (ANZAC Day Thursday, 25 April)

- 5:45am – Dawn Service at the Cenotaph

- 9:30am – Assemble for a 9.30am march in Clarence Street opposite Stella Motel, Clarence Street, for march to Cenotaph

- 9:35am – Commemoration Service to commence at completion of the march

Followed by morning tea at Yamba RSL Hall - Contact: Donna Ford – 0498 330 024

CHATSWORTH ISLAND (ANZAC Day, Thursday 25 April)

- 5:15am – Dawn service at the Cenotaph

Followed by a sausage sizzle - Contact: John Goodwin – 0419 282 555

Byron Shire

Thursday, 25 April 2024 04:30 AM to 12:00 PM. Services will be held across the Byron Shire to commemorate ANZAC Day.

Bangalow

- 10:30am – March from the Bangalow Hotel to the Cenotaph

Brunswick Heads

- 4:30am – March from the RSL Hall to the Cenotaph

Byron Bay

- 5:30am – Meet at the memorial Gates in Tennyson Street

- 10:30am – Meet at the memorial Gates in Tennyson Street

Mullumbimby

- 4:30am – Meet at the Cenotaph in Dalley Street

- 11:00am – March from Railway Station to the Cenotaph in Dalley Street.

Ballina Shire

- 5:30 AM – Dawn Service

Join us at the RSL Memorial Park Cenotaph for the first commemorative event of ANZAC Day. This service marks the time men of the ANZAC approached the Gallipoli beach and honors the traditional ‘stand-to’ ritual.

- 6:00 AM – Poppy Collection / Ballina RSL Breakfast

After the Dawn Service, collect your poppies from the ANZAC structure and enjoy a “In The Trenches Breakfast” at the Ballina RSL club for just $5. Open to the public – no bookings!

- 10:30 AM – ANZAC March

The ANZAC Day March will start at the far end of River Street, near Woolworths, moving towards the RSL and Memorial Park.

- 10:55 AM – ANZAC Day Service

The main service will be held at RSL Memorial Park adjacent to the Ballina RSL Club.

- 11:18 AM – RAAF Fly Past

- 11:30 AM – Ballina RSL Lunch

Conclude the morning’s commemorations with lunch at the Ballina RSL Club.

- 2:00 PM – Brownie & Friends’ Two-Up

Join us for a game of two-up at Brownie’s. Learn the rules and participate in this traditional ANZAC Day betting game. Open to all of legal gambling age.

Additional Information: Open to the public. All are welcome to join in remembrance and honor of our veterans.

Tweed Heads & Coolangatta

Dawn Service 5.45am

Held at Chris Cunningham Park, Wharf Street, Tweed Heads

Anzac Day Service 10.55am – 11.45am

Held at Chris Cunningham Park, Wharf Street, Tweed Heads

Burringbar – Old Bakery at 0845hrs for the march to the Memorial. Service to commence at 0900hrs. Refreshments and Bowls at the Sports Club after the service.

Cudgen – Assemble at Crescent Street at 0410 hrs. March to service at Collier Street Cenotaph at 0428hrs.

Kingscliff dawn – Assemble at Turnock Street at 0555hrs. Service at Kingscliff War Memorial. Breakfast at the Kingscliff Beach Bowls Club at 0700hrs.

Kingscliff main – Assemble at 1000hrs. March commencing at 1020hrs. Service at the Memorial at 1100hrs. Cars available for non-marchers.

Murwillumbah dawn – Assemble at War Memorial at 0520hrs. Breakfast in the Services Club at 0615hrs. Veterans and children under 12 free, others $5.

Murwillumbah main – Marchers assemble in Brisbane Street. Schools and other organisations assemble Main Street, opposite the Post Office at 1010hrs. March off at 1030hrs for Cenotaph Service at 1045hrs. Transport available for non-marchers at the assembly area.

Pottsville – Assemble at 0730hrs at Pottsville Beach Chemist. March off 0745hrs for the service at 0800hrs at the Cenotaph ANZAC Park. Breakfast at Pottsville Beach Sports Club after the service.

Tumbulgum – Memorial Gates 0430hrs. Breakfast in the hotel after the service.

Tweed Heads – Assemble on pathway behind Chris Cunningham Park at 0545hrs. Short wreath laying service at Chris Cunningham Park at 0630hrs.

🎖 Tweed Heads – Assemble in Boundary Street at 1000hrs, march off at 1030hrs down Boundary Street, left into Wharf Street and left to the Memorial in Chris Cunningham Park. Service of Remembrance from 1100hrs.

Tyalgum – Memorial 0515hrs. Breakfast in the hotel after the service.

Uki – War Memorial 0420hrs. Breakfast in the hall after the service.

These services offer a poignant reminder of the sacrifices made by our armed forces and provide an opportunity for community members of all ages to come together in remembrance.

For more local news, click here.

Lennox Head News

Lennox Park’s fresh and modern upgrade

Published

1 month agoon

27 March 2024By

Liam

Lennox Park’s fresh and modern upgrade

The Lennox Park upgrade is now complete, and the park fully reopened following a major overhaul.

The upgraded park includes:

- New architecturally designed bus stop and toilet amenities.

- Upgraded electrical and stormwater connections.

- New boardwalk and seating.

- New accessible pathways and seating.

- Improved landscaping and new arbour.

The much-loved shelter shed has undergone significant work to bring it back to its former glory.

“The renovation of the shelter shed was a much bigger task than anticipated due to the age and condition of the structure,” explained Ballina Shire Council Mayor, Sharon Cadwallader.

“However, we were able to significantly improve its functionality, look and feel while retaining its original design in line with Council’s resolution from November 2022.

“The shelter shed renovation ties in with the overall park upgrade and previous stages of the Lennox Village Vision project. Now it is fresh, functional, and ready to be enjoyed by the community for many years to come.”

The Lennox Head Heritage Committee has designed and procured a plaque that has been installed inside the shelter shed as part of the renovation. The plaque acknowledges the Lennox Head Centenary.

Meanwhile the new amenities block, which has been completely rebuilt from the original structure, will significantly improve accessibility.

“The new amenities include a family change room with shower, bench and baby change table, unisex accessible toilet, and two ambulant toilets.”

The Lennox Park upgrade is now complete, and the park fully reopened following a major overhaul.

Indigenous language artworks have been installed throughout the park.

“This is a continuation of the original ‘storyline’ concept of the broader Lennox Village Vision,” said Cr Cadwallader.

“The Aboriginal language words are etched into pedestrian footpaths, seating and as a backdrop to the bus shelter area.”

The words are based on the broader Bundjalung language and includes some words specific to the Nyangbal of the Lower Richmond, as such some spelling and pronunciation may vary from the neighbouring language dialects.

The artworks were produced by Ricky Cook, a local Nyangbal Elder and linguist who has been working in education for the past 40 years teaching on Bundjalung Country.

“Language goes with Country; they go hand in hand. Knowing language helps us better understand Country,” said Ricky.

“We are tremendously thankful to Ricky for his amazing work on this project and can’t wait for residents and visitors to explore these new features,” said Cr Cadwallader.

The Lennox Park upgrade was Stage 7 of the Lennox Village Vision project.

The final part of the Lennox Village Vision project will see the Rural Fire Service site on the corner of Park Lane and Mackney Lane converted into new public carparking spaces, once the RFS facility has been moved to its new site off Hutley Drive.

Further information will be provided to businesses and residents closer to the commencement date of these works.

Following the completion of these final works, Ballina Shire Council will host an official opening to celebrate the Lennox Village Vision project.

For more information visit here.

For more local Lennox Head news, click here.

Lennox Head News

Winning streak continues for Lennox Head para surfer Joel Taylor

Published

2 months agoon

13 March 2024By

Liam

Winning streak continues for Lennox Head para surfer Joel Taylor

By Sarah Waters

The decision to pick up a surfboard and get back in the ocean again has amounted to four huge accolades in the space of six months for Lennox Head bodyboarder, turned para surfer, Joel Taylor.

Last month, Joel, 43, was awarded Male Para Surfer of the Year at The Australian Surfing Awards held at Bondi Pavilion.

The prestigious awards ceremony, now in its 60th year, honours the country’s top surfers and those who have made a significant contribution to the sport behind the scenes.

Joel described the night as ‘epic’ as he caught up with friends and rubbed shoulders with Australian surfing greats.

“Celebrating our achievements put an exclamation point on a really successful 2023 for me,” he said.

“Receiving the award just topped it off. I was so stoked when my name was read out, I couldn’t wipe the cheesy grin off my face (laughs).

“I only started para surfing 18 months ago… to win the Australian Title, World Title, [Ballina Shire] Citizen of the Year and Para Surfer of the Year all within the last six months still blows my mind.”

Joel surfed to victory at The 2023 ISA World Para Surfing Championships

Joel’s story of triumph in the face of adversity first captured the surfing community’s attention when he won The Australian Para Surfing Title after a 20-year hiatus from the sport.

In his late teens/early twenties he was making a name for himself as the country’s rising star of bodyboarding.

But his promising career was ripped away in the lead up to the 2001 Pipeline Pro bodyboarding competition in Hawaii.

It was the first big swell of the season, and Joel caught the first wave of the set, but there was no water on the reef.

He described being in a barrel when he was hit by a powerful, shock wave, which planted him feet first on the notoriously shallow reef.

At 21 years of age, he was suddenly left with the physical and mental pain of knowing he’d never walk again after he injured his spinal cord in the freak accident.

Although his love for the ocean never disappeared, getting back into it again with a board in hand, seemed like an almost impossible task as he navigated his new reality of being confined to a wheelchair.

Dark years followed, but Joel focused his energy on the sport in a different way and created his own bodyboarding-inspired clothing line.

His now well-known business, Unite Clothing, occupied a large part of his life for two decades.

But, when he became a father, he decided his two young boys, Jay and Sunny, weren’t going to miss out on experiencing the thrill of the ocean.

With the help of his mates, he adapted a surfboard and made his way back into the waves.

Despite, the 20-year gap since he last stepped foot in the ocean, Joel said it was like nothing had changed and he could still use his upper body strength to power through the surf.

Lennox Head local Joel Taylor has rounded off his incredible comeback to surfing after being announced the Male Para Surfer of the Year at The Australian Surfing Awards in Bondi last month.

His unfulfilled talent and competitive side still lingered.

Joel decided to see what he was still capable of and entered the Australian Para Surfing Titles in 2023.

After only 12 months of training, he won.

The win granted him entry into The ISA World Para Surfing Championships team.

An unwavering determination to be a world champion led him to victory on the world stage.

After five days of intense competition, he was crowned The 2023 ISA World Para Surfing Champion in the Men’s Prone 1 Division.

“With the full support of my family, I put everything I had into achieving my goal of winning the world championship last year -a dream I’d had since I was 13 years old,” he said.

Joel’s remarkable comeback to the sport was recognised locally on January 26, this year, when he was named Ballina Shire’s Citizen of the Year.

A month later, his achievements culminated when he was named Male Para Surfer of the Year at the Australian Surfing Awards on February 28.

For more local Lennox Head news, click here.

NRTimes Online

Advertisment

The Northern Rivers Times Newspaper Edition 199

Public Invited to Review and Comment on Council’s Draft Budget and Operational Plan

Private Health Insurance Costs Under Scrutiny as Premiums and Profits Soar

Anzac Day Services Northern Rivers – Comprehensive Guide for the Region

Jewellery Design Centre Launches “Tell Our Stories” to Celebrate Lismore’s History

Lifeline Opens Northern Rivers Warehouse and Shop in Goonellabah

A NEW TWEED HEADS

Toyota Supra: Get Ready For A Fully Electric Version In 2025

Northern Rivers Local Health District COVID-19 update

Northern Rivers COVID-19 update

Fears proposed residential tower will ‘obliterate’ Tweed neighbourhood’s amenity and charm

COVID-19 Vaccination Clinic now open at Lismore Square

National News Australia

Teenager Charged with Terrorism Offence After Sydney Church Stabbing

Teenager Charged with Terrorism Offence After Sydney Church Stabbing In a significant development, a 16-year-old adolescent has been formally charged...

What do you do if you are the first on the scene of a crash, or arrive before emergency services?

What do you do if you are the first on the scene of a crash, or arrive before emergency services?...

Next major step in reforming emergency services funding

Next major step in reforming emergency services funding The public is invited to have their say on the best...

Latest News

-

Tweed Shire News2 years ago

Tweed Shire News2 years agoA NEW TWEED HEADS

-

Motoring News1 year ago

Motoring News1 year agoToyota Supra: Get Ready For A Fully Electric Version In 2025

-

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years agoNorthern Rivers Local Health District COVID-19 update

-

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years agoNorthern Rivers COVID-19 update

-

Northern Rivers Local News3 years ago

Northern Rivers Local News3 years agoFears proposed residential tower will ‘obliterate’ Tweed neighbourhood’s amenity and charm

-

Health News3 years ago

Health News3 years agoCOVID-19 Vaccination Clinic now open at Lismore Square

-

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years agoLismore Family Medical Practice employee close contact

-

NSW Breaking News3 years ago

NSW Breaking News3 years agoVale: Former NSW prison boss Ron Woodham