CSIRO scientists sequence first ever Spotted Handfish genome

Researchers at CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency, have successfully mapped the complete genome of the rare Spotted Handfish (Brachionichthys hirsutus), a critically endangered species native to Tasmania.

Once abundant off Tasmania’s southeast coast, this unique fish has seen its population drop dramatically, becoming the first marine species to be classified as critically endangered in 1996. It’s now estimated that fewer than 2,000 individuals remain in the wild.

The steep decline of the Spotted Handfish is linked to historical fishing practices, coastal development, climate change, and the introduction of invasive species. The newly sequenced genome, achieved through CSIRO’s Applied Genomics Initiative (AGI), will be a vital tool in conservation efforts.

CSIRO Senior Research Scientist, Dr. Gunjan Pandey, emphasized that this breakthrough will support ongoing efforts to increase the population and track genetic diversity.

“The genome helps us understand how an organism functions,” Dr Pandey said.

“It provides a foundation for understanding gene expression in daily life and offers insights into its evolutionary history.

“With the genome, we can assist with species detection, monitor populations, and even estimate the fish’s lifespan.”

Principal Investigator, Carlie Devine, who specialises in the conservation and management of the Spotted Handfish, said this rich genetic information will help inform conservation strategy over the long term.

“Conservation measures are expanding to include genetics,” Ms Devine said.

“Recognising a multidisciplinary approach alongside ecology research is essential for effective conservation of threatened species.”

Dr Pandey said the opportunity to sequence the genome of the elusive animal arose when a Spotted Handfish passed away of natural causes in captivity.

“Marine species like the Spotted Handfish are notoriously difficult to work with,” Dr Pandey said.

“The DNA degrades rapidly and becomes contaminated with microorganisms.

“This makes assembling a pure genome extremely challenging.”

The team successfully sequenced the full genome using only a small sample of low-quality DNA, applying a method known as the low-input protocol. This achievement was made in collaboration with the Biomolecular Resource Facility at the Australian National University.

“We are one of only three teams globally using this protocol,” Dr Pandey said.

“We customised the entire process – from the set-up of the lab to the bioinformatics software – to sequence a high-quality genome from poor-quality DNA.

“What used to take six to twelve months, we can now accomplish in days. This technology holds huge promise for our understanding and conservation of endangered species across Australia and around the world.”

Since 1997, CSIRO scientists have been closely monitoring nine distinct populations of the Spotted Handfish within the Derwent Estuary.

Their comprehensive conservation efforts involve a combination of a captive breeding program and innovative techniques for restoring the fish’s natural habitat.

Tweed Shire News2 years ago

Tweed Shire News2 years ago

Motoring News2 years ago

Motoring News2 years ago

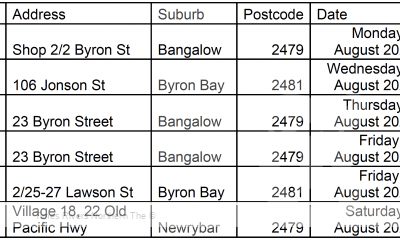

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

Northern Rivers Local News3 years ago

Northern Rivers Local News3 years ago

Health News3 years ago

Health News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

NSW Breaking News3 years ago

NSW Breaking News3 years ago