Workforce barriers tripping up young Australians and how to overcome them

Only half of young people feel confident in achieving their current or future career aspirations due to workforce barriers, new research has found.

This, coupled with a youth unemployment rate of 9.7% as of May 20242, underscores the critical need for targeted support and resources to equip young individuals with the foundational skills essential for navigating today’s complex job market.

For young people, particularly those from marginalised groups like Indigenous youth and women, there are additional barriers that exacerbate the challenge in securing employment and advancing careers including things like systemic inequities, limited access to quality education and training as well as pervasive social biases.

For example, recent studies have shown that 37% of women working in predominantly male environments report experiencing gender-based competence challenges3.

Employment services provider atWork Australia is addressing these challenges head-on by spotlighting the empowerment of young talent in preparation for World Youth Skills Day on 15 July, providing comprehensive support to young individuals, ensuring they have the necessary skills and assistance to confidently enter the workforce.

Over the last year, atWork Australia has supported over 7,300 young people (aged 25 years or younger) on their individual employment journey across metropolitan and regional Australia. Trends show that hospitality, warehousing and retail are the most appealing industries for young people to seek out. atWork Australia celebrates and applauds youth transition to all industries as each individual embarks on their employment and career journey.

One inspiring example is atWork Australia client, 18-year-old Yasmine, a determined Indigenous young woman from Mount Druitt, New South Wales. Through atWork Australia’s guidance, Yasmine defied odds and successfully entered the traditionally male-dominated mechanical industry.

Yasmine’s journey, starting from when she left school in Year 10, it reflects her resilience in overcoming significant challenges. Initial barriers included securing additional work hours and attending appointments due to financial constraints. Yasmine found crucial support from atWork Australia for emotional, mental and educational barriers as well as practical needs like food vouchers and travel costs4.

“atWork Australia has been a tremendous support for me,” Yasmine shared. “They kept me informed about job opportunities and reached out to discuss potential roles. It was empowering to be able to communicate my interests and preferences directly to them.”

Navigating her way through interviews and her initial week on the job, Yasmine benefitted from the guidance of atWork Australia’s Indigenous Connections team, who provided essential mentorship and support.

Despite encountering scepticism and doubts as a woman in a male-dominated field, Yasmine persevered, impressing her colleagues with her skills and determination.

“At 18, there were moments of self-doubt, especially being an 18-year-old female in this industry, but with atWork Australia’s unwavering support, I gained confidence and pushed through,” Yasmine reflected.

atWork Australia will continue to assist Yasmine until she feels fully settled in her new role and is committed to supporting her journey towards achieving her long-term goal of saving for a house deposit.

Yasmine’s story exemplifies the transformative impact of tailored support and mentorship in empowering young individuals to thrive in challenging environments.

atWork Australia is dedicated to providing comprehensive support to young individuals, ensuring they have the necessary skills and assistance to confidently enter the workforce.

To find out more about atWork Australia’s support services, please visit: www.atworkaustralia.com.au. Additionally, you can listen to any of the podcasts from the ‘Candid Conversations with Shaun Pianta’ podcast series here where atWork Australia Brand Ambassador and Paralympian, Shaun Pianta, speaks about his employment journey, following a life-changing holiday.

For more business news, click here.

Tweed Shire News2 years ago

Tweed Shire News2 years ago

Motoring News1 year ago

Motoring News1 year ago

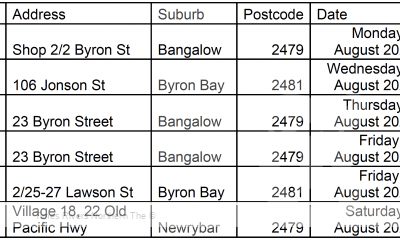

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

Northern Rivers Local News3 years ago

Northern Rivers Local News3 years ago

Health News3 years ago

Health News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

COVID-19 Northern Rivers News3 years ago

NSW Breaking News3 years ago

NSW Breaking News3 years ago